Voices of Wounded Knee

Lone Horn (aka “One Horn” )

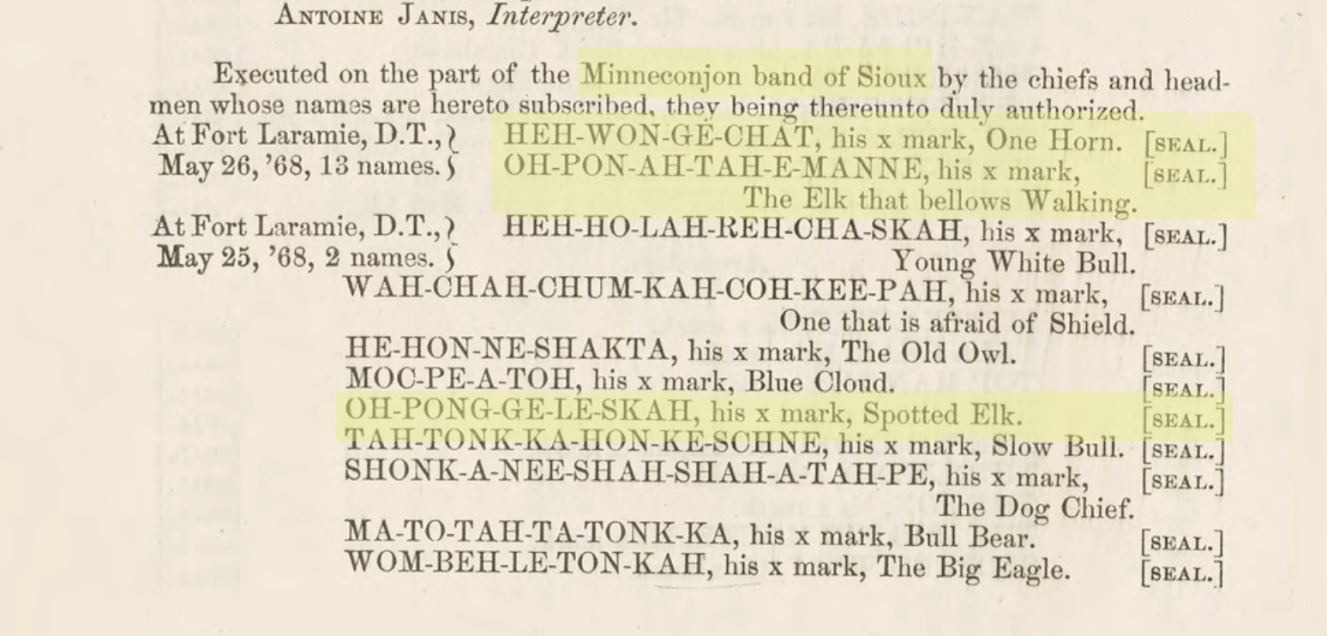

Lone Horn was a respected Minneconjou Lakȟóta leader and peace chief during a period of intense pressure on Lakȟóta lands and lifeways. In the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty signatory list for the Minneconjou, he appears under the treaty-era rendering “One Horn” (Heh-Won-Ge-Chat), reflecting how his name was recorded at the time. Lone Horn is remembered as a leader who carried responsibility for his people through diplomacy, delegation work, and the difficult transition into the reservation era.

Within our family, Lone Horn has always been understood as the father of Chief Spotted Elk, Uŋpȟáŋ Glešká (often written Unpan Gleska (and signed oh-pong-ga-leshka on the treaty), known later in records as Big Foot. Some historians have suggested that Lone Horn may have been an uncle who adopted and raised Spotted Elk rather than his biological father. That remains an open question in parts of the written record and is still being researched through documents, oral history, and descendant knowledge.

Lakȟóta kinship is real and binding: fatherhood includes responsibility, care, teaching, and one’s place within the tióšpaye (extended family). Adoption and raising a child carry full relational meaning. At the same time, lineal descent and heirship also matter - not as a colonial standard, but as protection against erasure. Clear documentation of parentage and descent helps prevent misidentification, helps descendants keep their histories intact, and helps avoid the very real harms that come from confusion - including families being separated in the record, identities being overwritten by outsiders, and even relatives unknowingly marrying within their own extended lines when genealogy is obscured. For this reason, we honor Lakȟóta kinship while also continuing careful documentation of lineal descent wherever the evidence allows.

Lone Horn’s legacy lives on through descendants and through the leadership tradition he embodied - leadership rooted in responsibility to the people. His life and relationships cannot be fully understood through colonial records alone, but through Lakȟóta ways of knowing alongside careful, transparent research that keeps families connected to their true histories.

Fort Laramie Treaty (1868)

The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 was a pivotal agreement between the United States and multiple Lakȟóta bands, including the Minneconjou, intended to establish peace following years of armed conflict and to recognize Lakȟóta territorial rights. The treaty affirmed the Great Sioux Reservation and acknowledged Lakȟóta authority over vast territories in what is now South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Montana.

Minneconjou Signatories

The treaty record for the Minneconjou band includes the marks of several closely related leaders, demonstrating both political leadership and extended kinship ties within the band. Among those recorded are:

Heh-Won-Ge-Chat (One Horn / Lone Horn)

Oh-Pong-Ge-Le-Skah (Spotted Elk)

Oh-Pon-Ah-Tah-E-Manne (She Elk Voice Walking / Elk That Bellows Walking)

These individuals appear as distinct signatories, each recognized by U.S. officials as authorized leaders acting on behalf of the Minneconjou. Treaty-era spellings reflect phonetic renderings by non-Lakȟóta interpreters and do not always correspond precisely to modern Lakȟóta orthography.

Kinship and Leadership

Oral history and family tradition hold that Lone Horn, Spotted Elk, and She Elk Voice Walking (Elk That Bellows Walking) were closely related. Within Lakȟóta society, leadership was often shared among extended family networks, and kinship carried political, ceremonial, and protective responsibilities. Adoption and caregiving relationships were fully recognized forms of parenthood, and authority did not depend solely on biological descent.

At the same time, the treaty record makes clear that these men were separate individuals, each exercising independent leadership. Their presence together in the treaty underscores the importance of distinguishing identities rather than merging them, a distinction that has frequently been lost in later historical accounts.

Importance of Lineal Identification

While Lakȟóta kinship structures are foundational, lineal descent and heirship remain critical for historical accuracy and descendant protection. When identities are conflated or substituted—particularly in colonial records—families risk erasure, misattribution, and long-term harm. Clear identification safeguards descendants, preserves inheritance lines, and prevents future confusion in genealogical and community records.

The Fort Laramie Treaty signatures serve as fixed documentary anchors that, when read alongside oral history and descendant testimony, help ensure that Minneconjou leaders such as Lone Horn, Spotted Elk, and She Elk Voice Walking are remembered as distinct yet closely related figures within their historical and cultural context.

I